History

"...the ongoing and relentless efforts of republican Turkey to destroy any remaining Armenian historical monuments and to eliminate any evidence of historic Armenia. The markers and monuments testifying to the existence of the Armenian people in their homeland have thus become the final victims of the genocide begun in 1915."

- Robert Jebejian

This beautiful monastery, also known as "Beşkilise" (Turkish for "Five Churches"), was spread out over three spurs of rock within a gorge about 25km south-west of Ani and a little to the west of the village of Digor (formerly called Tekor). The monastery had a total of five churches, all of them domed and carefully built out of finely cut stone. The churches were called: Saint Karapet, Saint Astucacin, Saint Stephanos, Saint Gregory, and Saint Sargis. Only the church of Saint Sargis is standing today. The churches have no inscriptions which provide information on the date and circumstances of the monastery's founding or the building of the individual churches. The monastery was abandoned after the Mongol invasions of the 13th century. In 1878, after the Russian conquest of the Kars region, Khtzkonk was returned to the Armenian Church. The buildings were renovated and religious life resumed within the monastery. New accommodation was erected for monks and pilgrims - these were built along the edge of the main spur, beside the river in the gorge below, and also to the north-west of the Saint Sargis church. The Monastery's DestructionThe fate of Khtzkonk is one of the clearest and most disturbing examples of the Turkish state's genocide of this region's Armenian population being later extended to their cultural monuments. The monastery remained in use until 1920, when the remaining Armenian population of the Kars region was expelled by the Turks. After this, the area became a restricted military zone that was closed to visitors (as late as 1984 a special permit was needed to travel to Digor). When the monastery was next visited by historians, in 1959, only one church, Saint Sargis, remained standing - and it was seriously damaged. It was reported that villagers at that time said the churches had been blown up by Turkish soldiers. The inhabitants of nearby Digor still (2002) say the same thing. There is little doubt that the destruction was caused by explosives. Lumps of masonry from the destroyed churches have been flung far from their original positions. The slopes between the spurs are filled with shattered fragments of stonework, chunks of inscription covered wall, fragments of columns, and bits of ornate sculpture. The damage to the St. Sargis church is even more indicative - the side walls of the apses and chapels have been blown outwards, evidently by explosives placed within them. The location of a dated piece of modern graffiti (positioned so that it was lit by a window that is now destroyed) suggests that the destruction took place sometime after 1955. The inhabitants of Digor are vague on the actual date, only saying "about 30 years ago". Some western academics, not wanting to upset Turkey and thus damage their career advancement, try to wriggle out of explaining Khtzkonk's destruction by inventing alternative reasons for the damage. For example, T. A. Sinclair in his 1987 book "Eastern Turkey, an Architectural and Archaeological Survey" wrote that the churches were destroyed by falling rocks. From where did these rocks fall? To where did these rocks disappear? And how did they manage to defy the laws of gravity by jumping over the Saint Sargis church in order to destroy its neighbours?Saint Sargis was badly shaken during the December 1988 earthquake; the concrete core of the building was shattered and the church is now in a state of near collapse. Most of the photographs on these pages are from before the earthquake. |

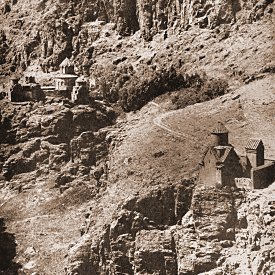

1. The monastery, photographed before 1920

3. The monastery seen from the west  4. Left to right are: St. Stephanos, St. Astucacin, St. Karapet, and St. Sargis - click for a larger photo  5. The monastery site today, looking to the west  6. Only one church remains - click for a larger photo |

The Individual Churches:Church of Saint John the Baptist

This was probably the oldest church in the monastery, and may date from as early as the seventh century or from the 10th century (although the umbrella-shaped roof over the dome must be later than this). The oldest inscription on its walls was dated 1001 (or 1006) and mentioned Queen Katranideh of Ani, the wife of King Gagik.

The church had a four apsed interior, with a domed roof whose drum rested on squinches. Only a small fragment of wall and the foundations of the apse survives today.

|

8. The church of Saint Stephanos

|

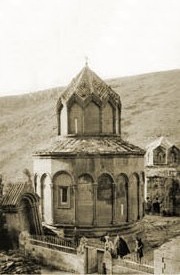

12. A photograph c1910 showing the church of Saint Sargis |

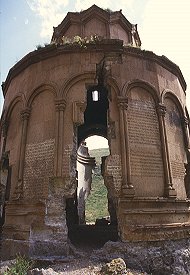

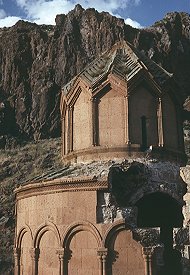

13. The church of Saint Sargis today - click for a larger photo |

14. Cracks in the northern facade - click for a larger photo |

15. Damage to the southern facade - click for a larger photo |

Church of Saint Sargis

"In the name of God, in the year 1214, I, Davit son of Grigor, general under the chief Zakaria, saw the splendour of the Holy monastery of Khtzkonk ... and I gave half the village of Vahanardzesh, which is in my possesion, to Surb Sargis church as a memorial to myself and my parents. Because of this, I, Hovhannes the abbot and vardapet, and the other brothers, have ordained that an annual liturgy should be celebrated by me in all the churches on the feasts of David, Hokob, Paughos and Petros, and the Holy Shoghakat without fail. If anyone opposes or obstructs this memorial, as much as God has blessed that man, may he be cursed."

- Inscription on the north face of the Saint Sargis church

This was the largest church in the monastery, and it is the only one still standing. It has no inscriptions that mention the date or circumstances of its construction. However, according to the 12th century historian Samuel of Ani, it was commissioned in 1025 by a Prince Sargis. The earliest inscription on its walls is dated 1033. Another inscription, from 1211, records the liberation of the monastery from the hands of the Muslims.

It is a domed, four-apsed, centrally-planned, church contained within a circular exterior. The dome rests on a drum supported on pendentives. This dome has an angular umbrella shaped roof - if this is also from 1025 then it is the earliest surviving example of this form of roof in an Armenian church.

There are small rooms on two levels in each of the four corners. The lower rooms were chapels. The upper rooms - accessed through small and hard to reach openings high in the interior wall - were probably used for the storage of valuables and also gave access to the roof of the church.

It is a domed, four-apsed, centrally-planned, church contained within a circular exterior. The dome rests on a drum supported on pendentives. This dome has an angular umbrella shaped roof - if this is also from 1025 then it is the earliest surviving example of this form of roof in an Armenian church.

There are small rooms on two levels in each of the four corners. The lower rooms were chapels. The upper rooms - accessed through small and hard to reach openings high in the interior wall - were probably used for the storage of valuables and also gave access to the roof of the church.

There is a window in each apse; on the interior these windows are framed by a highly unusual architectural moulding. This is in the form of a curved, open-bed pediment resting on columns embedded into the wall of the apse. Between the pediment and column is a strange entablature that appears to represent layers of turned wooden cylinders. The top of the pediment overlaps a moulded cornice that runs around the whole interior - such an overlapping of elements is also extremely unusual in Armenian architecture. The outside walls are encircled by graceful blind arcading that divides the facade into twenty sides. Incised into many of the flat surfaces between these arcades are long inscriptions written in large, clear, deeply carved lettering.Built beside the northern wall of the church was a large khatchkar set within an elaborate vaulted shrine. There was a similar monument on the south-eastern side of the church.A Final CommentThe Saint Sargis church was built at the end of the most flourishing period of the so-called "Ani School" of Armenian architecture.The quality of the construction and finish of the masonry in this church exceeds anything that survives at Ani. Its overall design is extremely well worked out, and the architectural details are also more refined, mature, and carved to a higher standard. It shows what might have been if historical circumstances had allowed architectural evolution to continue at Ani. (Many of these architectural ideas were taken up again when conditions allowed for the resumption of building activities in this region during the 13th century - so much so that this church was once considered to be from that later period). The impression given is of a building not made out of many individual blocks of stone, but carved, like an enormous sculpture, out of a single mass of creamy-orange rock. The design of Saint Sargis is praiseworthy, but the overall appearance of Khtzkonk must have been quite breathtaking. The layout of the monastery, perched at the edge of cliffs and encircled by even higher cliffs, presented an extraordinary picturesque harmony of architecture and environment. The rigorous geometry, smooth surfaces, and sharp edges of the five churches were a startling contrast to the natural landscape of the gorge that surrounded them, but at the same time they complemented and seemingly effortlessly integrated themselves into that environment. As a result of the deliberate destruction of Khtzkonk in the 1950s, all that is now left to reveal this are a few precious old photographs. |

|